Salary Benchmarking Mistakes That Cost You Top Talent

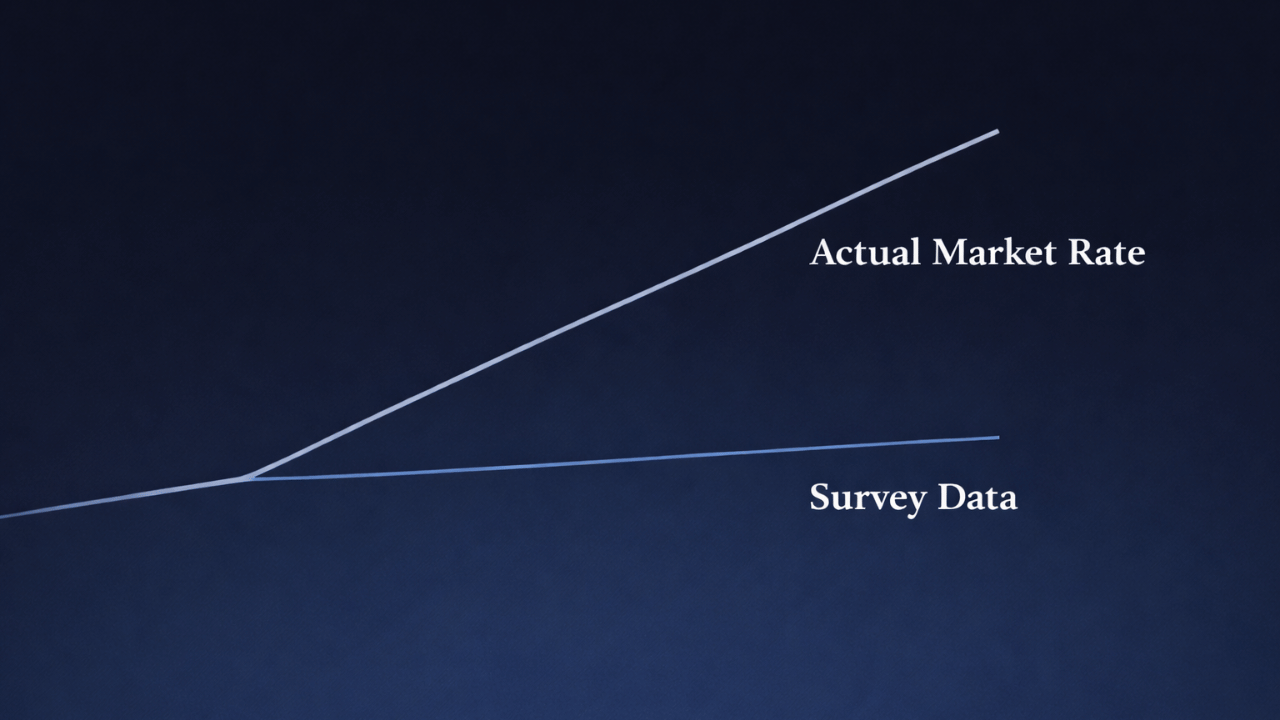

Your salary benchmarking data is already obsolete. By the time Glassdoor, Payscale, or your industry salary survey publishes its findings, the market has moved on. For most companies, this creates a systematic problem: you're using 18-24 month old data to make offers in today's market, which means could be underpaying by 10-15%. The result isn't just losing candidates; it's adverse selection. You're filtering out precisely the talent you most want to hire.

The mechanics of this failure are straightforward but rarely examined. Third-party salary surveys follow a predictable cycle: data collection takes 6-12 months as surveyors gather information from participating companies, then compilation and analysis takes another several months, and finally publication occurs. By the time you're looking at that neat percentile breakdown showing the 50th, 75th, and 90th percentiles for "Senior Accountant, 5-7 years experience," that data reflects compensation decisions made 18-24 months ago.

In stable markets, this lag might be manageable. But compensation markets are anything but stable, particularly for in-demand roles. When demand for specific skills surges (machine learning engineers, cloud architects, FP&A roles, specialized sales roles) market rates can move 15-20% in a single year. Your salary survey can't capture this. It's a rearview mirror in a market that requires looking forward.

The Adverse Selection Mechanism

Here's where the economic impact compounds. The candidates you most want to hire, the top performers with multiple options, know the real market rate because they interview constantly. They're talking to recruiters weekly, they have peers changing jobs and sharing offer details, and they understand what their skills command today, not 18 months ago. When you extend an offer based on survey data that's 10-15% below current market, these candidates reject immediately.

Who accepts?

Candidates fall into two categories: those who don't know the real market rate (which often correlates with less market exposure and fewer options), and those who know but can't command better offers. You've created an unintentional screening mechanism that filters for the candidates you least want.

The economics term for this is adverse selection, the same dynamic that plagues insurance markets and used car sales. When buyers and sellers have asymmetric information, the party with less information makes worse decisions. In this case, you're the party with less information, and you're systematically making worse hiring decisions as a result.

What Actually Determines Market Rate

Real market rates aren't found in surveys. They're discovered through actual market transactions. Three sources matter:

Competing offers your candidates receive.

When you lose a candidate and they share what they accepted instead, you're getting real-time market intelligence. If your $140,000 offer consistently loses to $160,000 offers, that's not negotiation variance - that's market rate.

What it actually takes to close your last 10 hires.

Track your offer acceptance rate by level and role. If you're extending offers to Controllers at $150,000 and they’re accepting 30% of the time, you're below market. If they're accepting 70-80% of the time, you're at or above market. The acceptance rate is direct market feedback.

Counter-offers from current employers.

When a candidate accepts your offer, then their current employer counters with exactly what you offered (or more), that's market rate validation. It also reveals that the candidate was previously underpaid, which is useful intelligence about compensation practices at competitor firms.

This is messy, qualitative data that doesn't fit neatly into a spreadsheet. But it's accurate in the way that matters: it reflects what you actually need to pay to close deals today.

The Survey Data Paradox

None of this means salary surveys are useless. They provide valuable directional guidance and help you understand rough relativities between roles and markets. A salary survey telling you that senior accountants in San Francisco typically earn 40-50% more than senior accountants in Atlanta is useful structural information.

The error is using surveys for precision pricing. When you set your offer at the 65th percentile of the survey data because that matches your compensation philosophy, you're confusing precision with accuracy. The survey might tell you that 65th percentile is $145,000, but if real market rate has moved to $160,000, your precise positioning at $145,000 is precisely wrong.

Better practice: Use surveys to establish broad bands (this role pays somewhere between $130,000-$170,000), then use real-time market intelligence to position within that band. The survey gives you the framework; actual recruiting conversations give you the price.

Market Velocity Varies by Role

Not all roles suffer equally from survey lag. Accounting roles in stable industries might move 2-3% annually, well within the error margin of survey data. Specialized technical roles in growing fields might move 15-20% annually, making survey data nearly worthless.

This creates a strategic imperative: know which of your roles operate in fast markets and which in slow markets. For slow markets, survey data is fine for precision pricing. For fast markets, you need real-time intelligence and willingness to move quickly when market rates shift.

Geographic markets also vary in velocity. Major tech hubs (San Francisco, New York, Seattle) typically see faster compensation movement than secondary markets. Remote work has complicated this further; what's the market rate for a remote position that could be filled from anywhere? Survey data struggles to answer this because the market is too new and too fragmented.

When to Pay Above Market

Market rate isn't always your target. Two scenarios justify paying above market:

Critical roles with talent scarcity.

If you're hiring a specialized role where qualified candidates are genuinely scarce (not just hard to find because you're looking in the wrong places), paying 75th-90th percentile or higher makes economic sense. The opportunity cost of the role staying unfilled exceeds the cost of premium compensation.

Speed to hire matters more than cost.

If time-to-fill creates substantial business cost (a VP Sales role unfilled during your peak selling season, a critical engineering hire blocking a product launch) paying above market to close quickly generates positive ROI. The incremental compensation cost is trivial compared to the revenue or opportunity cost of delay.

These decisions require actual economic analysis, not just anxiety about filling roles. Calculate what the unfilled role costs your business per month, compare it to the incremental cost of paying 75th vs. 50th percentile, and make a rational decision.

When Market Rate Is Fine

For roles where talent is abundant and candidates are relatively interchangeable, market rate (50th percentile) is perfectly adequate. You don't need to pay premium compensation for commodity skills in abundant supply.

This isn't dismissing these roles as unimportant; a role can be business-critical but still have abundant qualified candidates available. The compensation decision should reflect supply and demand economics, not how you feel about the role's importance.

Building Better Benchmarking Practices

Effective benchmarking requires multiple data sources and healthy skepticism of any single source:

Use survey data for directional guidance and band creation. Understand the broad range for each role and level, but don't anchor to specific percentiles.

Track your own offer acceptance rates. This is your most reliable real-time market indicator. Calculate acceptance rate by role, level, and compensation range. If acceptance rates drop when you offer below a certain threshold, that's your effective market floor.

Debrief every declined offer. When candidates reject your offer, find out what they accepted instead. Build this intelligence into your compensation database. Over time, you'll have better market data than any survey can provide.

Monitor what you're losing candidates to. Track which companies are winning talent from you and at what compensation levels. If you're consistently losing to the same competitors at 15% higher compensation, you have a market rate problem.

Network with peers in similar companies. Informal compensation discussions with other hiring managers and executives provide qualitative market intelligence that surveys miss. What are they paying? What's working? Where are they struggling?

Review quarterly, not annually. In fast-moving markets, annual compensation reviews mean you're behind market for 9-12 months every year. Quarterly reviews let you adjust more responsively.

The goal isn't perfect information; you'll never have that. The goal is good enough information to avoid systematic adverse selection. If your benchmarking approach is filtering out your best candidates because you're consistently 10-15% below market, you're making an expensive mistake that compounds over time.

Every mis-priced offer doesn't just cost you one candidate. It costs you the contribution that candidate would have made to your business, it forces you to restart the search process (which has substantial cost and delay), and it trains your hiring managers to distrust your compensation guidance. The true cost of bad benchmarking isn't the money you didn't spend on higher offers; it's the opportunity cost of the talent you didn't hire.