The Manager Quality Paradox: Why Your Best Employees Leave Your Worst Managers

Your CFO tracks employee turnover at the organizational level: survey scores, aggregate retention rates, company-wide compensation benchmarks. Meanwhile, your VP of Engineering just lost three senior developers in six months to the same team lead. Your Head of Sales watches high performers exit while C-players collect paychecks under managers who couldn't lead a parade.

This is the manager quality paradox: companies invest millions in organizational retention strategies while the actual driver of attrition, individual manager quality, operates unchecked. Research from Gallup shows that managers influence at least 75% of the reasons employees voluntarily leave. Yet retention budgets flow to engagement surveys, culture committees, and compensation adjustments - interventions that treat turnover as an organizational problem rather than a managerial one.

The economics are perverse. Your best employees, who have the most employment options, leave bad managers first. Your worst employees, with fewer alternatives, stay. Over time, bad managers systematically select for mediocrity, creating a quality inversion that compounds across hiring cycles. The manager you refused to address isn't just driving away talent; they're fundamentally altering your workforce composition.

The Data: Manager Quality Drives Attrition

The relationship between management and turnover isn't speculative. According to Gallup's research on voluntary exits, 42% of employees who left their jobs say their manager or organization could have prevented their departure. More significantly, when Gallup examined the factors driving voluntary turnover, they found managers influence at least three-quarters of the reasons people quit.

This finding challenges the standard narrative that compensation drives retention. When employees cite "pay and benefits" as their reason for leaving, it's often downstream of management failure. Gallup's data shows that perceived pay inequity intensifies when employees believe their colleagues aren't pulling their weight, a direct management problem. The employee isn't leaving because they're underpaid in absolute terms; they're leaving because their manager tolerates low performers while expecting high performers to compensate.

The LinkedIn 2024 Workforce Confidence Survey found that employees citing "my manager" as the reason for considering a job change outnumber those citing compensation. This isn't because salary doesn't matter; it's because bad management makes every other workplace friction intolerable. The manager who micromanages, hoards information, takes credit for team wins, or fails to develop talent creates conditions where even competitive pay can't retain good people.

Why Manager Quality Matters More Than Compensation

Standard retention economics suggest that raising compensation should reduce turnover. But research consistently shows that manager quality explains more variance in retention than pay levels. Here's why:

Managers control the daily experience of work.

While the CFO sets compensation bands and HR designs benefits packages, managers determine whether employees get interesting projects, autonomy to make decisions, visibility with senior leadership, and opportunities to develop new skills. A bad manager can make a well-paid role miserable. A good manager can make a modestly paid role fulfilling enough that employees turn down higher offers.

Manager quality affects future earnings potential.

High performers evaluate jobs not just on current compensation but on career trajectory. A manager who develops talent, provides growth opportunities, and advocates for promotions increases an employee's lifetime earnings. A manager who stagnates careers, blocks transfers, or fails to provide meaningful work reduces future earning potential, making exit economically rational even with a short-term pay cut.

Bad managers create negative option value.

In behavioral economics, option value refers to the benefit of preserving future choices. A good manager creates option value: employees stay because the role might lead to better opportunities within the organization. A bad manager destroys option value: employees recognize that staying means foreclosing on external opportunities while gaining nothing internally. The calculus shifts from "what do I gain by leaving?" to "what do I lose by staying?"

What Makes a Bad Manager: Specific Behaviors That Drive Turnover

The "bad manager" diagnosis is too vague for decision-making. CFOs need to know which management behaviors actually drive turnover so they can measure and address them. Here are the specific patterns that consistently predict attrition:

Micromanagement.

Managers who require approval for minor decisions, demand constant status updates, or refuse to delegate meaningful work signal to high performers that the organization doesn't trust their judgment. The economic cost isn't just employee frustration; it's the opportunity cost of senior talent spending time on work that junior employees could handle. When talented employees realize they're being paid for judgment they're not allowed to exercise, they leave for roles that actually use their capabilities.

Lack of development opportunities.

Research from LinkedIn found that employees who rate their company's internal mobility program as excellent are 26% more likely to say they wouldn't consider changing jobs. But internal mobility depends entirely on whether managers create growth opportunities, support lateral moves, or block talented employees from transferring. Managers who hoard talent, refuse to train successors, or fail to advocate for their team's advancement force employees into a binary choice: stagnate or leave. Most high performers choose to leave.

Credit-taking and blame-deflecting.

Managers who claim credit for team successes while distancing themselves from failures create a toxic incentive structure. High performers recognize that their best work generates no reputational benefit while any setback will be attributed to them personally. The rational response is to leave for an environment where performance is accurately attributed.

Poor communication.

Gallup found that 45% of employees who voluntarily left their jobs reported that no manager or leader proactively discussed their job satisfaction, performance, or future with the organization in the three months before their departure. When managers fail to provide context, give feedback, or discuss career progression, employees operate with incomplete information about their standing and prospects. Uncertainty drives turnover; employees leave not because they definitively want to leave, but because staying feels like an uncalculated risk.

Favoritism and unfair treatment.

When managers allocate opportunities, compensation, or recognition based on personal relationships rather than performance, they create adverse selection. High performers recognize that merit doesn't predict rewards, so effort becomes irrational. Why work harder if the manager's favorite gets the promotion regardless? The highest performers, who have the most to lose from non-meritocratic systems, exit first.

No autonomy or decision-making authority.

Employees with advanced degrees and significant experience expect discretion over how they accomplish their work. Managers who impose rigid processes, demand adherence to specific methods, or refuse to accept alternative approaches signal that the organization values compliance over results. High performers, who typically have strong opinions about optimal work methods, find this intolerable and leave for roles with greater autonomy.

The Quality Inversion Problem

Bad managers don't just drive average turnover; they drive selective turnover that systematically degrades workforce quality. Here's the mechanism:

High performers have more options.

Employees with strong skills, established networks, and proven track records receive more recruiting outreach, get more interviews, and convert interviews to offers at higher rates. A senior software engineer with five years of experience and projects on GitHub gets contacted by recruiters weekly. A mediocre engineer with the same tenure gets contacted monthly. When both report to the same terrible manager, the senior engineer can exit within weeks. The mediocre engineer stays because finding a comparable role takes months.

Low performers have fewer options.

Employees with weak skills, thin networks, and limited accomplishments struggle to find alternative employment. They receive less recruiting attention, perform poorly in interviews, and have fewer offers to evaluate. Even under a bad manager, staying employed beats the risk of unemployment. The bad manager's team becomes a reservoir for employees who can't leave rather than those who choose to stay.

The composition effect compounds over time.

As high performers exit and low performers accumulate, team quality declines. This decline makes the team less attractive to strong external candidates; talented hires can tell from interviews that they'd be working with weak peers. The bad manager's team enters a death spiral: deteriorating quality makes recruitment harder, which further degrades quality, which makes the manager even less likely to be replaced (leadership assumes the manager can't be that bad if they're successfully hiring).

Consider the mathematics: if a manager loses 30% of their team annually and the departures skew toward the top quartile of performers, after three years the team composition has radically changed. The manager hasn't improved. The employees who had leverage to leave have left. The employees who remain are those with the fewest external options - which typically correlates with lower performance.

Why Companies Don't Solve the Manager Problem

If bad managers are the primary driver of turnover, why do they persist? The answer lies in measurement difficulty, political barriers, and structural misalignment.

Manager quality is hard to measure.

Revenue per employee, project delivery timelines, and budget adherence are quantifiable. Manager quality is not. Companies attempt to measure it through engagement surveys, skip-level meetings, and 360-degree feedback, but these instruments are noisy. Employees hesitate to criticize managers who control their performance reviews, promotions, and project assignments. Survey responses skew positive. By the time the data suggests a manager is problematic, high performers have already left.

Even retention metrics are imperfect signals. A manager with low turnover might be excellent, or might be managing a team of employees with few external options. A manager with high turnover might be terrible, or might be managing a team of flight risks inherited from a previous regime. Isolating manager quality from confounding factors requires sophisticated analysis that most organizations don't perform.

Political and organizational barriers prevent removal.

Removing a bad manager is organizationally expensive. It requires documenting performance failures, navigating HR processes, risking legal exposure, and managing the disruption of a leadership transition. It also requires someone senior to take accountability for the hiring mistake. The VP who promoted the bad manager has reputational incentives to defend that decision rather than admit error.

Bad managers also develop protective relationships. They cultivate favor with senior leadership through visibility management, ensuring executives see their successes while failures remain hidden at the team level. They build alliances with peers who might face scrutiny if the organization started removing underperforming managers. The result is organizational inertia: everyone knows the manager is problematic, but no one has sufficient incentive to act.

The Peter Principle: promoting technical experts into management.

In a study published in the Quarterly Journal of Economics, researchers Alan Benson, Danielle Li, and Kelly Shue analyzed promotion decisions across 214 firms and 40,000 sales workers. They found clear evidence of the Peter Principle: firms systematically promoted top-performing salespeople into management roles, despite the fact that sales performance negatively predicted managerial effectiveness.

The data showed that when a salesperson's pre-promotion sales doubled, their subordinates' post-promotion sales performance declined by 7.5%. The best salespeople (confident, achievement-oriented, focused on personal results) became the worst managers. Yet firms continued to promote based on sales performance rather than managerial potential because it appeared "fair" and because alternative criteria (collaboration experience, leadership aptitude) were harder to measure and easier to game.

The Peter Principle creates a structural misalignment: the promotion process selects for individual contributors with minimal management capability. Organizations reward technical excellence with management roles that require entirely different skills. The promoted employee is now incompetent at their job (managing people) while their previous source of competence (technical work) is no longer their responsibility. Turnover follows predictably.

Solutions That Work

Addressing the manager quality paradox requires measurement systems, political will, and structural changes that most organizations resist. But the economics are clear: fixing bad managers is cheaper than absorbing the turnover they create.

Manager effectiveness metrics.

Organizations need leading indicators of manager quality that capture retention before it becomes a crisis. Two metrics outperform alternatives:

Team retention rate by manager. Track voluntary turnover at the manager level, not the organizational level. If one manager loses 40% of their team annually while peers lose 10%, investigate. Adjust for confounding factors (new team, inherited problems, industry-wide talent wars), but don't dismiss persistent patterns. A manager with consistently high turnover is a costly liability regardless of their technical skills.

Skip-level feedback quality. Schedule quarterly skip-level conversations where senior leaders meet with team members two levels down without their direct manager present. Ask specific questions: "What decisions would you make differently if you had more autonomy?" "What skills are you trying to develop?" "What would make you consider leaving?" Pattern-match responses across team members. If three people independently cite the same management failure, it's not a coincidence.

Management training that's actually good.

Most management training fails because it teaches generic skills (active listening, emotional intelligence, strategic thinking) without addressing the specific behaviors that drive turnover. Effective management training is behavioral and context-specific.

Train managers to conduct meaningful one-on-ones focused on career development, not project status. Teach them to delegate by outcomes rather than tasks, "increase conversion rate by 10%" rather than "update the email template", so employees have autonomy over methods. Provide frameworks for giving difficult feedback without resorting to vague praise or harsh criticism. Measure training effectiveness by tracking team retention before and after intervention.

Removing bad managers (controversial but necessary).

Some managers cannot be trained into competence. They lack the interpersonal skills, strategic judgment, or willingness to develop others that effective management requires. When coaching and feedback don't produce improvement, organizations must be willing to remove managers from leadership roles.

This doesn't mean termination; it means creating paths for technical experts to remain individual contributors without managing people. Many bad managers would gladly return to technical work if the organization didn't treat individual contributor roles as dead ends. The issue isn't the person; it's the role mismatch.

Calculate the economics: if a bad manager drives 30% annual turnover on a 10-person team when the baseline is 10%, they're creating two excess departures per year. At a replacement cost of 150% of salary (recruiting, lost productivity, training), a team with an average salary of $100,000 faces $300,000 in annual turnover costs attributable to management quality. Paying severance or transitioning the manager to an individual contributor role costs less.

Alternative IC tracks.

The Peter Principle persists because organizations use promotion to management as the primary path for career advancement and compensation growth. High performers face a dilemma: accept a management role they're poorly suited for, or plateau in compensation and influence.

Create parallel career tracks where individual contributors can reach compensation and status equivalent to senior management without managing people. Staff Engineer, Distinguished Designer, Principal Researcher - titles that signal seniority without requiring leadership of others. This allows organizations to retain and reward technical excellence without forcing square pegs into round management holes.

The Retention Investment That Actually Matters

CFOs evaluating retention investments face dozens of options: raise compensation across the board, improve benefits packages, fund engagement initiatives, expand remote work policies. These interventions have measurable costs and uncertain returns.

Improving manager quality has the highest ROI of any retention strategy because it addresses the mechanism that drives turnover. An organization that replaces its worst-performing 10% of managers (measured by team retention, skip-level feedback, and subordinate development) eliminates the single largest source of preventable attrition.

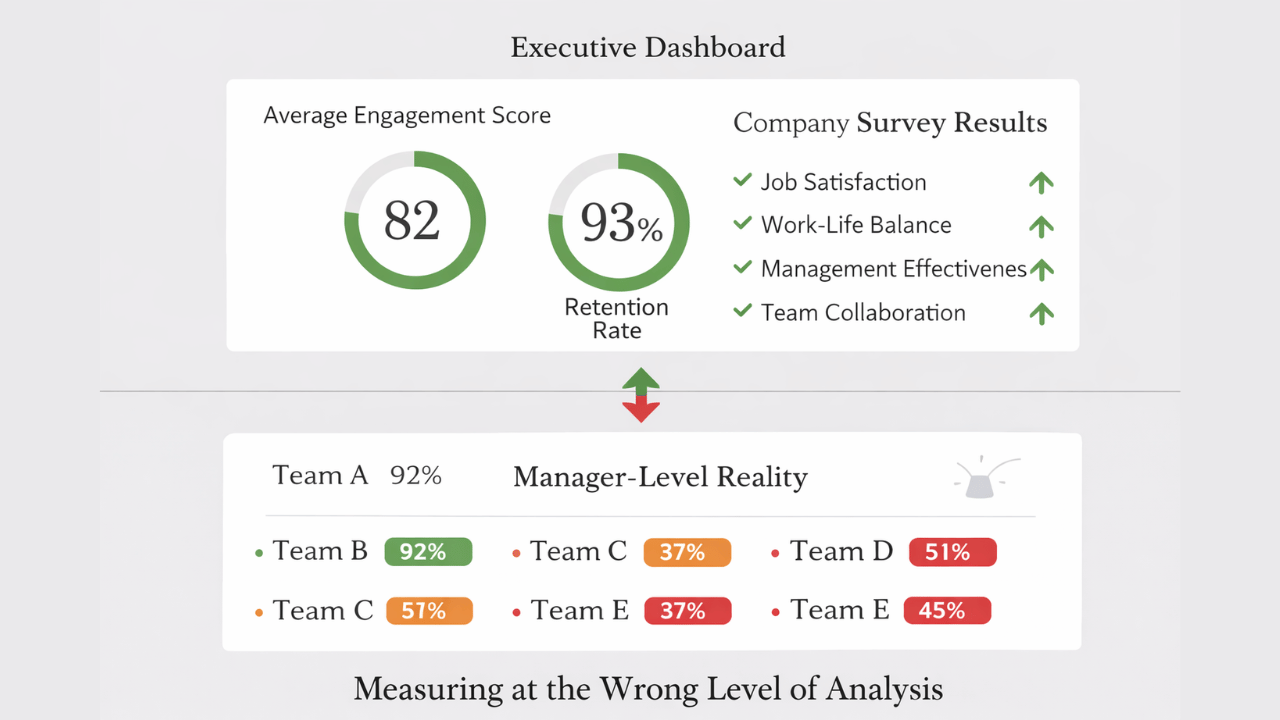

The paradox is that companies optimize retention at the wrong level. They measure engagement at the organizational level, adjust compensation at the departmental level, and intervene with culture initiatives at the company level - while the actual variance in retention occurs at the manager level. The CFO who funds another engagement survey while ignoring manager-driven turnover is optimizing for metrics that don't predict outcomes.

Your best employees leave your worst managers. Your worst employees stay. The quality inversion isn't a talent problem; it's a management problem. And management problems, unlike talent problems, are solvable with measurement, accountability, and the willingness to act on what the data reveals.