Why Your Best People Quit: Information Asymmetry in Retention Strategy

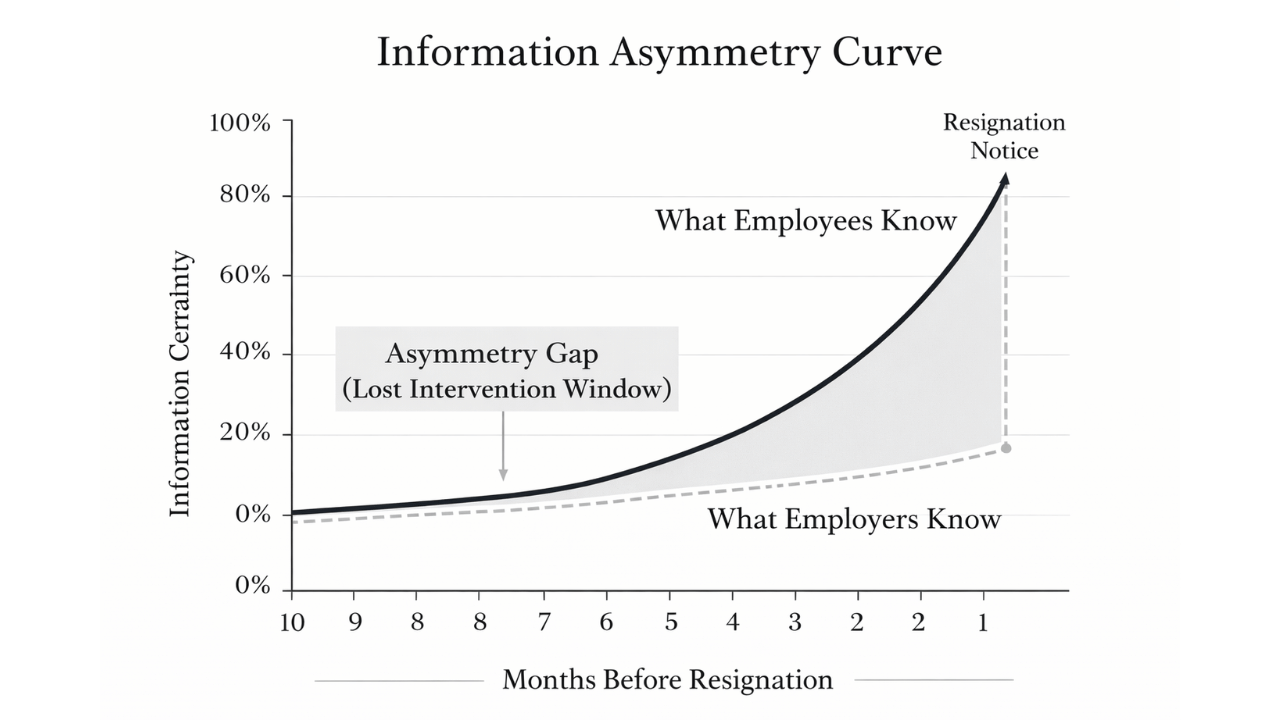

By the time your high performer gives two weeks' notice, the decision to leave was made months ago. You were operating with incomplete information while they had perfect clarity. This information gap, where employees know their plans and you don't, makes most retention efforts reactive theater rather than preventive strategy.

The Asymmetry Problem

Information asymmetry occurs when one party in a transaction has materially better information than the other. In employment, this asymmetry runs one direction: employees have complete information about their job satisfaction, market options, and intention to leave. Employers have delayed, filtered signals from engagement surveys, skip-level meetings, and manager observations.

George Akerlof won the Nobel Prize demonstrating how information asymmetry creates market failures. In his "Market for Lemons" model, sellers know a car's quality while buyers don't, leading to adverse selection. The employment relationship has the same structure, but inverted: the employee (seller of labor) knows their commitment level and alternative options. The employer (buyer of labor) learns about flight risk only after the employee has already mentally checked out.

This creates a predictable pattern: by the time you know someone is leaving, it's too late to address the underlying causes. Your retention efforts become damage control, not prevention.

The Decision Window You're Missing

Research on employee turnover suggests most resignation decisions aren't impulsive; they follow a months-long deliberation process. While the exact timeline varies by individual and circumstance, the pattern is consistent: employees typically spend several months evaluating their situation, exploring alternatives, and building conviction before giving notice.

The process looks like this:

Months 1-3: Dissatisfaction emerges.

Something changes - a bad project assignment, a passed-over promotion, a new manager, organizational restructuring. The employee starts questioning whether to stay. During this window, they're still engaged but increasingly aware of friction points.

Months 4-6: Active evaluation begins.

They update their LinkedIn profile, respond to recruiter messages, research market rates, talk to peers at other companies. They're building information about alternatives while maintaining normal job performance. This is your last preventive window, but you don't know you're in it.

Months 7-9: Commitment to leaving.

They're interviewing, negotiating offers, planning their departure. They've made the psychological exit even if they haven't given notice. Any retention effort here is too late; you're trying to change a decision that's already been made.

Month 10+: Notice.

They've accepted another offer, provided notice, and begun transitioning work. You finally have perfect information about their intent to leave, at the exact moment when that information is least useful.

The asymmetry is complete: you discover their flight risk precisely when you can no longer prevent their departure.

Why Your Current Methods Fail

Organizations rely on two primary information channels for retention: engagement surveys and exit interviews. Both fail for predictable reasons.

Engagement Surveys: Lagging and Filtered

Annual or quarterly engagement surveys suffer from three structural problems:

First, timing lag. If you survey employees quarterly, you have at best a 90-day-old snapshot of satisfaction. An employee who became dissatisfied in February won't show up in your data until the March survey, which you don't analyze until April, which doesn't reach managers until May. By then, they've been exploring alternatives for three months.

Second, social desirability bias. Employees know that survey responses, despite anonymity promises, could be traced back to them in small teams. They're not going to honestly report "I'm actively interviewing elsewhere" or "My manager is incompetent" when that feedback might damage relationships or future references. Survey responses are filtered through political calculation.

Third, aggregation obscures individual risk. Even if your survey captures dissatisfaction, it's reported as team or department averages. An 85% engagement score for your engineering department looks healthy, but it masks that your three best engineers are at 40% engagement and actively interviewing. The aggregate data smooths away the signal you need.

Engagement surveys tell you what people were willing to admit they felt three months ago. That's not actionable intelligence.

Exit Interviews: Honest Feedback After It's Useless

Exit interviews fail for an even simpler reason: employees have no incentive to be honest.

When someone gives notice, their primary concern is preserving professional relationships and securing a positive reference. Telling their soon-to-be-former manager "you're the reason I'm leaving" or telling HR "the compensation is below market" burns bridges they might need. So they offer socially acceptable explanations: "opportunity for growth," "new challenge," "personal reasons."

This creates a systematic bias in exit interview data. The real reasons for departure (manager quality problems, compensation gaps, lack of development opportunities, organizational dysfunction) get sanitized into generic platitudes. You end up with data that's both perfectly honest (they really are leaving for a "new opportunity") and completely useless (you learn nothing about what you could have done differently).

Exit interviews give you honest feedback after the employee has already decided the relationship is over and you can't use that information to retain them. It's the wrong information at the wrong time.

The Signals You're Missing

While you're waiting for survey results and exit interviews, employees are broadcasting their flight risk through behavioral signals. Most managers miss them because they're not looking, or because the signals are individually ambiguous. But in combination, they form a clear pattern.

LinkedIn Profile Updates

When an employee who hasn't touched their LinkedIn profile in two years suddenly adds new skills, updates their headline, or changes their profile photo, something has shifted. They're preparing to be visible to recruiters and hiring managers. This is especially telling when coupled with increased activity - liking posts, sharing content, accepting new connections.

The timing matters. If LinkedIn activity increases after a reorganization, a passed-over promotion, or a manager change, you're seeing the early stages of exit planning.

Calendar Mysterious Appointments

High performers don't suddenly develop frequent dental appointments or take multiple long lunches without explanation. When someone who typically works through lunch starts blocking calendar time for "personal appointments" or working from home on unusual days, they're likely interviewing.

The pattern to watch: recurring blocks during business hours, especially if they're vague ("appointment," "out of office," "personal time") and especially if the employee is otherwise highly engaged and productive.

Sudden Policy Interest

When an employee starts asking HR questions they've never asked before, pay attention to the content. Questions about PTO accrual, vesting schedules, 401(k) portability, COBRA coverage, or non-compete clauses signal departure planning. They're doing due diligence before giving notice.

Similarly, if someone requests copies of performance reviews, asks about reference policies, or inquires about exit procedures, they're preparing to leave, not hypothetically, but concretely.

Behavioral Shifts Managers Don't Notice

The most subtle signals are behavioral changes that managers attribute to other causes:

Reduced advocacy: Someone who used to champion projects or push back on bad ideas becomes passive. They stop caring about outcomes because they won't be there to see them.

Shorter time horizons: They stop volunteering for long-term projects or make comments like "that's a conversation for next quarter" when it's only September.

Decreased social investment: They skip optional team events, stop grabbing coffee with colleagues, pull back from informal collaboration. They're beginning the emotional exit.

Increased documentation: They start writing things down, creating runbooks, or organizing information in ways they never did before. They're preparing for knowledge transfer.

Individually, these could be stress, burnout, or distraction. In combination with other signals, they indicate someone is psychologically checking out.

Peer Departures and Clustering Effects

Turnover clusters. When one person on a team leaves, the probability of others leaving increases sharply. This happens for two reasons:

First, information sharing. Departing employees tell trusted peers where they're going, what they're earning, and what opportunities exist. This gives remaining team members perfect information about market alternatives they didn't have before.

Second, workload redistribution. When someone leaves, their work gets redistributed to remaining team members, typically without compensation adjustment. This increases dissatisfaction precisely when team members are learning about better alternatives.

If you see one departure from a team, assume others are evaluating their options. The information asymmetry just narrowed; your remaining employees now know something about market conditions that you don't know they know.

Leading vs. Lagging Indicators

The difference between leading and lagging indicators explains why retention efforts fail.

Lagging indicators tell you about outcomes that already happened: resignation notices, exit interview feedback, turnover rates. They're perfect measurements of past failure but provide no predictive power for future retention.

Leading indicators predict future outcomes: manager effectiveness scores, career development conversations, market compensation positioning, promotion velocity relative to tenure. They give you time to intervene before the resignation decision is made.

Most organizations measure lagging indicators exclusively. They track turnover rates, calculate time-to-fill for departed roles, and analyze exit interview themes. All of this is backward-looking analysis of decisions they can't change.

The actionable data is forward-looking: Which teams have the highest ratio of high performers to development opportunities? Which managers have team members with the longest time since promotion? Which employees are reaching tenure points associated with elevated flight risk (typically 18-24 months and 3-4 years)? Which roles have market compensation moving faster than your internal adjustments?

These questions identify future flight risk while you still have time to address the underlying causes.

Creating Information Channels That Actually Work

If engagement surveys and exit interviews don't work, what does? You need information channels with three characteristics: they're continuous (not quarterly), they're candid (people tell the truth), and they're specific (you learn about individual flight risk, not department averages).

Manager Quality as an Information System

The single most effective retention information channel is manager quality, because direct managers are the only people in an organization who have continuous, unfiltered access to employee satisfaction.

Good managers notice behavioral changes, have regular career development conversations, understand market dynamics for their team members, and maintain relationships where employees will be honest about dissatisfaction before they start interviewing. Bad managers don't notice anything until they receive the resignation email.

This is why the commonly cited finding that "people leave managers, not companies" is both true and understates the problem. It's not just that bad managers drive attrition; it's that bad managers are blind to attrition risk until it's too late, while good managers see it coming and can intervene.

The practical implication: improving manager quality is not just a retention strategy, it's an information strategy. Better managers give you better, faster, more accurate data about flight risk.

Stay Conversations, Not Exit Interviews

Exit interviews collect honest feedback (at best) after it's useless. Stay conversations collect honest feedback while you can still use it.

A stay conversation is a structured discussion between a manager and employee focused on one question: What would make you leave, and what would make you stay? This inverts the information flow; instead of waiting for the employee to volunteer dissatisfaction, you're explicitly asking about retention factors.

The conversation covers:

What aspects of the role are most and least satisfying

What career development goals the employee has and whether they see a path to them here

What would cause them to consider external opportunities

What concerns or frustrations they have about the team, role, or organization

The key is frequency and psychological safety. These conversations need to happen at least semi-annually and employees need to believe they can be honest without political consequences. That requires manager training and organizational commitment to actually address the concerns that surface.

Market Intelligence and Compensation Positioning

You can reduce information asymmetry by gathering the same market intelligence your employees have. This means:

Regular compensation benchmarking for your specific roles and locations (not generic "market data")

Tracking where departing employees go and what they're earning

Monitoring which competitors are hiring for your skillsets

Understanding career path and title progression at peer companies

When you know that your Senior Engineers are 15% below market and your competitors just raised their ranges, you have leading indicator data about flight risk. You can address compensation gaps before people start interviewing.

Turnover Pattern Analysis

Past turnover patterns predict future turnover risk. If you analyze departures over the past 2-3 years, you'll find patterns:

Specific tenure points with elevated departure risk

Seasonal patterns (people leave after bonus season, after performance reviews)

Triggering events (reorganizations, manager changes, policy changes)

Team-specific or manager-specific elevated turnover

These patterns give you a framework for identifying current flight risk. If your data shows elevated departure risk at 18-24 months tenure, and you have five high performers approaching that window, you know where to focus retention conversations.

The Economic Stakes

Information asymmetry in retention creates measurable economic waste. Organizations spend retention budgets reactively (counter-offers, replacement recruiting, knowledge loss) instead of preventively. The magnitude of this waste depends on your turnover costs, but the pattern is universal: you spend more money solving retention problems you discover late than you would preventing problems you discovered early.

Consider a scenario: You have a Senior Engineer earning $150,000 who becomes dissatisfied in January. You don't discover this until they give notice in September. Your options at that point are: (1) make a counter-offer that has a 70-80% chance of failing within 18 months, or (2) accept a $225,000-300,000 replacement cost (recruiting, training, productivity loss).

If you had discovered the dissatisfaction in February through a stay conversation or manager observation, your options would have been: (1) career development plan, (2) compensation adjustment to market rate, (3) scope expansion, or (4) manager change. All of these cost less than $100,000 and have higher success rates than counter-offers.

The difference between early intervention and late intervention is $100,000+ in avoided costs, per departure prevented. Across an organization with even modest turnover, this compounds to millions in annual waste from operating with delayed information.

Conclusion: Closing the Information Gap

You will never have perfect information about employee retention risk; employees will always know their intentions before you do. But you can narrow the gap from months to weeks, and from complete surprise to anticipated risk.

The path forward requires three commitments:

First, invest in leading indicators, not lagging indicators. Measure manager quality, career development velocity, compensation positioning, and tenure risk patterns. These predict future turnover while you can still prevent it.

Second, create continuous information channels. Replace annual surveys and exit interviews with stay conversations, manager effectiveness assessment, and market intelligence gathering. Move from quarterly snapshots to continuous monitoring.

Third, accept that manager quality is your information infrastructure. Good managers are early warning systems for retention risk. Bad managers are blind to attrition until it's too late. Improving manager effectiveness is not just an engagement initiative; it's an economic imperative for reducing the cost of delayed information.

The goal is not to eliminate information asymmetry; that's impossible in an employment relationship where people have agency and privacy. The goal is to reduce the time between when an employee decides to leave and when you discover that decision. Shorter discovery time means lower intervention costs and higher prevention success rates.

In retention strategy, information is not just power - it's profitability. The organizations that solve the information asymmetry problem spend less on reactive retention and lose fewer high performers to preventable departures. Those that don't solve it keep learning about flight risk at the exact moment when that knowledge is least valuable: when they receive two weeks' notice.

Key Takeaways:

Employees decide to leave 6-9 months before giving notice—you're always operating with delayed information

Engagement surveys and exit interviews fail because they collect filtered, lagging data that's not actionable

Leading indicators (manager quality, career development, compensation positioning) predict future turnover while you can still prevent it

Stay conversations, manager effectiveness, and market intelligence create continuous information channels that reduce discovery time

The economic cost of information asymmetry is the difference between early intervention (low cost, high success) and late intervention (high cost, low success)